One of the more challenging aspects of the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) to administer is intermittent bonding. Companies that employ hourly populations for service or production, such as retail, manufacturing, and call centers, find this provision especially demanding. Employers must consider how regulations for the FMLA and paid family and medical leave (PFML) programs may interact with their policies and programs.

Under FMLA §825.120(b), an eligible employee must take FMLA leave for birth, placement, and bonding as a continuous block of leave unless the employer allows leave to be taken on an intermittent basis or reduced schedule basis. Intermittent leave is leave taken in separate blocks of time.1 A reduced leave schedule reduces the usual number of working hours per workweek or workday.2 For the sake of convenience, both types of leave will be referred to as intermittent leave in this article.

Many employers rely on this provision to help mitigate operational disruptions that stem from intermittent absences, and it’s permissible! But consider what is truly happening when this provision is applied. The complexities of multiple time-away programs may have the opposite effect of disallowing this provision and enabling employees to remain off work for a longer period. Or worse, result in regulatory noncompliance.

Unpaid Statutory Leave

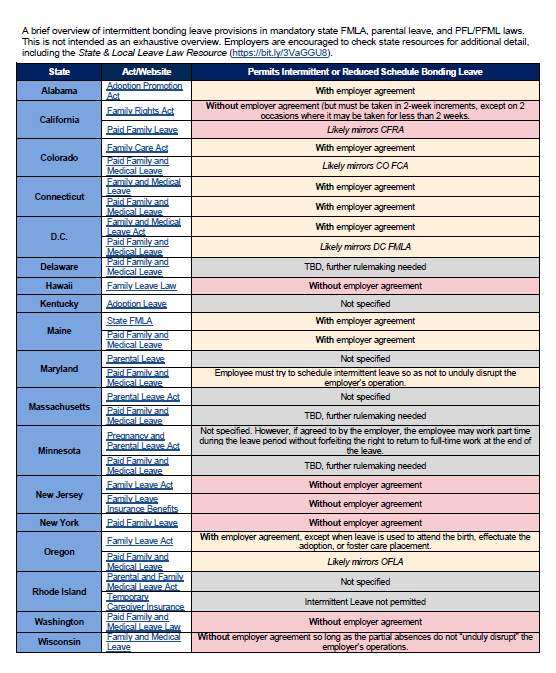

A number of states have family and medical leave laws, and unlike the FMLA, some of these laws require employers to allow employees to take bonding leave intermittently.3 This is an important factor to consider when designing company leave policies as the intent of a company policy may be to limit intermittent bonding use to a minimum number of hours and/or days. It should also be part of ongoing reviews since employer agreement is not a required factor in an employee’s ability to take intermittent bonding in states like California, Hawaii, New Jersey, Oregon, and Wisconsin. Furthermore, under the California Family Rights Act, bonding leave may be used in two-week increments except on two occasions when employees may use a smaller increment of time.

Statutory PFML

It’s hard to ignore the ever-growing presence of state-mandated PFML programs and their effect on employer leave programs. The absence of a federally mandated PFML program means that employers must work diligently to ensure benefit program coordination occurs within the confines of multiple state programs. As with unpaid statutory leave laws, many state PFML programs do not require employers to agree to an employee using leave intermittently. But a handful of states (i.e., Connecticut, Maine, and Massachusetts) do impose this caveat. Rhode Island’s Temporary Caregiver Insurance program stands out from the rest of the state paid family leave laws because it does not allow intermittent leave to be used under any circumstance. Additionally, many states have stipulated minimum increments of leave within their programs. For example, New Jersey Family Leave Insurance and New York State Paid Family Leave must be used in full-day increments, and Colorado PFML allows one-hour increments.

So where does this leave employers? And what occurs when policies do not align and/or conflict?

Living in Harmony

As a general rule, employees should be able to use leave in the most favorable way permissible. That means if company policy does not allow intermittent bonding but the employee works in a state with a law that permits it, the employee must be able to take bonding leave intermittently. This approach will facilitate alignment across federal, state, and employer programs and ensure that FMLA and state leave requests can run concurrently.

However, organizational hurdles may prevent an employer from taking this approach. Let’s consider the following scenario: An Oregon employee requests intermittent bonding leave. Company policy dictates that the manager must approve intermittent bonding under the FMLA, and the company paid parental leave (PPL) policy requires time to be taken in one-week increments. Under Oregon’s Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance (PFMLI) program, the employee is allowed to use time in one-day increments. This leave is also job protected if the employee has been employed for at least 90 days.

Let’s now assume that the employee’s manager does not approve the employee’s request. The employee is approved for intermittent bonding through the state’s PFMLI program but neither the FMLA nor company PPL runs concurrently. It is likely that this employee is now absent intermittently (with job protection) and will continue to maintain a full bank of FMLA and PPL time. It’s also very possible that this employee will later use both FMLA and PPL for this same bonding event, thereby stacking benefit programs, which would result in additional job-protected time off.

Employers should consider whether it is more disruptive to allow intermittent leave or to work around an employee’s extended period of leave. While this is just one scenario, the message is clear: Do not ignore the potential effects of conflicting policies. As a best practice, adding clarifying language to company policies helps ensure programs run concurrently, such as: FMLA runs concurrently with other types of leave. While leave entitlements under the company’s policy and any applicable state laws generally run concurrently, company policy does not supersede any state laws that provide greater rights.

Spousal Sharing

Employers should also consider the potential impact of the spousal sharing limitation, another bonding-related FMLA regulation. Under FMLA §825.120(a)(3), employers may limit eligible spouses who are employed by the same covered employer to a combined total of 12 workweeks of leave within a 12-month period for the following FMLA-qualifying reasons:

- Placement of a son or daughter with the employee for adoption or foster care, and bonding with the newly placed child; and

- Care of a parent with a serious health condition.

Eligible spouses who work for the same employer are also limited to a combined total of 26 workweeks of leave in a single 12-month period to care for a covered service member with a serious injury or illness if each spouse is a parent, spouse, son, daughter, or next of kin of the service member. When spouses take military caregiver leave as well as other FMLA leave in the same leave year, each spouse is subject to the combined limitations for the reasons for leave listed above.

The Department of Labor (DOL) issued a final rule in 2015 revising the regulatory definition of “spouse” under the FMLA to include all individuals in legal marriages, regardless of where they live. Specifically, the definition of spouse is now a husband or wife as defined or recognized in the state where the individual was married (“place of celebration”) and specifically includes individuals in same-sex and common law marriages. Spouse also includes a husband or wife in a marriage that was validly entered into outside of the United States, if the marriage could have been entered into in at least one state.4

Administrative Complexities

Administration of the spousal sharing limitation provision in practice is largely problematic. For starters, many employers do not specifically track which employees are spouses in a way that is easily accessible for leave administration purposes. For smaller organizations or when leave is managed in-house, and where the means exist within the process to validate marital status (for example, within a human resources information system) before approving leave, administration may be more manageable. Otherwise, when an employee requests leave, the application of the sharing provision relies heavily on an employee answering truthfully when asked if they have a spouse who is also taking leave from the same employer and for the same reason. Herein lies the risk.

There is also the potential for disparate treatment if the provision is not applied consistently across the eligible employee population. And finally, there is always the water cooler chatter that could have a negative effect on an employee’s perception of the provision. Imagine when Amber returns from maternity leave and tells everyone how nice it was that the company lets both parents take 12 weeks of bonding leave. Meanwhile, Chrissy had to split that time with her spouse and between caring for her ailing parent. Chrissy is not going to be pleased and is not going to keep this quiet.

In the absence of an ironclad process, employers should consider removing any spousal sharing limitations. Overall, benefits are becoming more employee-friendly and more accessible, two aspects that support removal of the limitations.

What’s to Come?

Bills related to repealing this provision of the FMLA have been introduced in Congress for the last few years. In 2023, the Fair Access for Individuals to Receive (FAIR) Leave Act was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives (H.R. 5037) and U.S. Senate (S. 2574). Both bills were referred to committee, and there has been no activity since.5,6

Additionally, employers should be aware of the current trend to expand the definition of covered family members in state paid and unpaid leave laws. Most recently, Minnesota’s PFML and paid sick leave laws and Maine’s PFML laws (all of which passed and were enacted in 2023) include expansive definitions of a covered family member.

The FMLA was enacted more than 30 years ago. But the continuing evolution of state paid and unpaid leave programs requires employers to analyze existing policies, provisions, and practices carefully and deliberately across the organization and down to the leader level.

The one thing that remains consistent with leave programs is that there’s never a dull moment in the management of employee absences. Employers should ensure that potential conflicts of mandated leave provisions and business operations are considered annually as part of policy reviews and as new mandates are passed and implemented.

References

- Code of Federal Regulations. Part 825 — The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993. Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-29/subtitle-B/chapter-V/subchapter-C/part-825

- U.S. Government Publishing Office, Title 29, Code of Federal Regulations. Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-29/subtitle-B/chapter-V/subchapter-C/part-825/subpart-B/section-825.202

- DMEC. State and Local Leave Laws Resource. Retrieved from https://dmec.org/resources/state-and-local-leave-laws-resource/

- Department of Labor. Final Rule to Revise the Definition of “Spouse” Under the FMLA (2015). Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla/spouse

- U.S. House of Representatives. H.R. 5037: FAIR Leave Act. Retrieved from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/118/hr5037

- U.S. Senate. S. 2574: Fair Access for Individuals to Receive Leave Act. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2574/text?s=1&r=8